Heidi Salzwedel, a graduate of the Stellenbosch and Rhodes Universities, is an art and design educator, and an artist/writer who lives and works in Cape Town. She met Maryke in the Cape Winelands. Maryke van Velden is a visual artist and curator.

Heidi Salzwedel: What has been the path, artistically and spiritually, that has led you to where you are today?

Maryke van Velden: In short: growing up in a rather eccentric missionary household, with a theologian father and a singer-painter mother. In my childhood home one would likely smell oil paints, linseed oil and genuine turpentine. But at the same time this is where I experienced first-hand what practical theology looks like. This instilled in me a reverence for liturgy as well as deep appreciation for the arts.

The privilege of having grown up outside of South Africa (in Malawi) pre-1994 only dawned on me long after we had left there. From a very young age I was integrated into multicultural, multiracial and multireligious communities and befriended people across ideological boundaries. Sadly, I would most likely not have had this opportunity in my home country at the time due to the difficulties posed by the apartheid government. I do believe that this experience kindled in me esteem for people from various cultural backgrounds and a lifelong desire to bridge divergent sectors of society, whether through social networking, the arts, or the church.

HS: Tell us a bit more about your educational background?

MvV: After school, and a gap year spent in Europe, I did a degree in fine arts at Stellenbosch University, followed by a master’s degree in illustration at the same institution (2012, cum laude). I have since taken part in a few group exhibitions (mostly local), worked in curriculum development for deaf learners, lectured drawing at various tertiary institutions, and am currently working as creative director and curator at a nonprofit cultural centre in my hometown, Stellenbosch. I continue to produce art when time allows.

I am tremendously grateful to have found my “artistic and spiritual” feet by joining a small local community of artists and biblical practitioners, called “40 Stones.” This initiative has brought into being a series of professional and thought-provoking art exhibitions of works by biblically-led artists in recent years; the last of which was the Transept show which featured in TBP, Issue 3. In this social space I feel safe to think about, question, and deliberate on matters pertaining to both the arts and the Christian faith.

HS: What were your experiences of the pandemic and what artworks did you produce during the pandemic in response to them?

MvV: More than anything the pandemic brought to the surface various layers of loss. Initially, my experience was acute isolation and intense personal loss. As the period of strict lockdown subsided in South Africa, and various national regulations were loosened, personal loss made way for a realisation of the immense communal loss of our country and the globe. Hence, intuitively a lot of what I produced artistically since the start of 2020 has touched on experiences of loss.

It has always been the contemplative physicality of the art-making process that I’ve been most drawn to and which is often of most value to me as a maker. At the start of the pandemic, I turned to art making partly as a means of processing loss, and partly as a way of keeping busy and centring my thoughts. I briefly discuss three works from this period, each rather different in nature.

During Easter weekend, 2020, I made a series of drawings of my “surrounds in captivity,” using red wine. One of these is titled I sat and I saw: it is good. This drawing represents a photograph I took at my then home: an empty plastic garden chair in the autumn garden. At the time South Africa was undergoing a strict national lockdown, which confined residents to their homes. The garden became a space of tranquil retreat, which I frequented. Making this drawing was a way of submissively embracing the imposed solitude, and also of escaping the ensuing anxiety. Through subtle symbolic references this work became both a prayer of anguish and a voice of comfort.

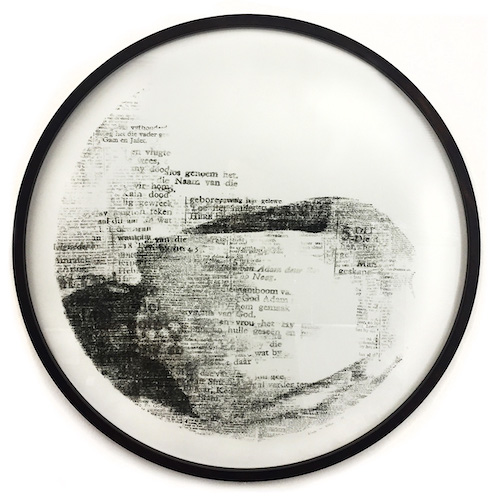

In response to the strangeness of social distancing and the reshaping of the nature of interaction, I went on to create a life-sized self-portrait of mourning. The composition comprises overlapping layers of scriptural text (primarily from Genesis 2) with varying intensities of toner, depicting my bare back as I lie in a foetal position.

The opening chapters of the book of Genesis were written to Jewish exiles who, under new rule, had begun questioning their identity. These passages touch on themes of birth and death, redemption and responsibility; all elements that revolve around relationships. During the period of solitude in which I created this work, I attempted to revisit the nature of my own relationships: with myself, with others, and with my maker.

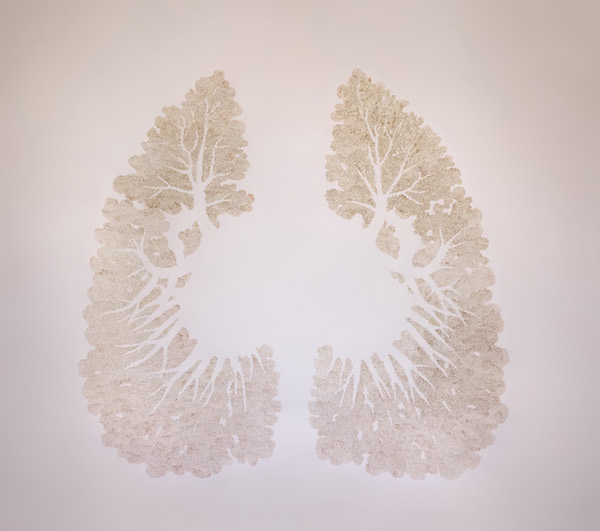

As the pandemic prolonged, I ruminated on the suffering I witnessed in the lives of friends and acquaintances who had lost loved ones due to COVID-19. Moved by the poignant New York Times cover graphic on 21 February 2021, just over a month after having lost a close friend to COVID-19, I decided to draw a meditation in memory of all the South Africans who had lost their lives to COVID-19 during the one-year period since the first recorded death in the country. From 28 March 2020 to 28 March 2021, 52 663 COVID-19 related deaths were officially recorded in South Africa.

I ventured into a drawing process that would last for weeks: through keeping meticulous count I shaped two enormous lungs out of tiny dots of blood; each representing one death to COVID-19 during the year that had passed. Breathing Prayer reflects on individual and communal loss.

HS: You use a variety of media – what motivates your experimentation and can you explain a bit more about how you used these different media in the three artworks?

MvV: As a particularly tactile-sensitive person, I find that I am often as intrigued by the media used in a work of art, as I am by the content represented. My art making has both an intuitive and a conceptual approach. I find that the choice of medium not only stimulates sensory intrigue, but it also challenges the viewer to consider it as a meaningful substance itself, instead of simply the transparent carrier of a message. My own uses of divergent media such as red wine, toner and blood – all which had originated from play and experimentation – are thus hermeneutical considerations.

The use of red wine (in I sat and I saw: it is good) for a work made during Easter has of course the obvious liturgical connotation of the body of Christ. I wanted to accentuate the solitude I experienced during Easter (2020); a time annually spent in devout reflection and among loved ones. The use of wine during this particular period seemed even weightier due to the national prohibition on alcohol sales at the start of the lockdown in 2020. I manipulated the density of the wine by both heating it and by diluting it in order to develop a broader range of monochrome tones.

Working with toner (in Body Becoming), which is used in laser printing, is a process I liken to a type of tactile exegesis; biblical text metamorphoses first into illegible texture and finally takes on an alternative form which asks to be read in a new (i.e., visual) language. Most of the knowledge we gather through reading is absorbed via printed text, and thus through toner. The slow physicality of continual manual “re-texting” echoes for me the narrative of biblical creation through God’s Word; toner becoming a mimicking substance from which “life is called forth.”

In Breathing Prayer, it was my intention to create something intricate and beautiful through the use of the deeply personal medium of blood, often considered to be impure. The use of blood seemed even more fitting as the resulting image would portray a vital organ. However, in this body part the passage of blood flow is absent; the metaphoric vines are indicated by negative space which ultimately merges with the central void. It is particularly the juxtaposing of this bodily substance with the silent mystery of a great unknown which I find significant.

HS: Is there anything you take from lockdown and the pandemic that gives you hope?

MvV: There is, indeed. The gruelling months of strict lockdown offered time (if not so much space) to process death and loss in various forms. For the first time after many dormant years, I felt almost forced to turn (back) to making art. This opened a space of rediscovery for me, for which I’m grateful as an artist.

I felt particularly encouraged by an experience I had during the time my Breathing Prayer work was exhibited at Transept, an exhibition in Somerset West (SA) in September 2021. The exhibition was held in a newly-built, modern church building. My piece, ironically, hung in the “cry room.” This intimate space, an annex to the atrium, became almost chapel-like: I installed a shelf with hundreds of small candles next to the framed drawing, inviting viewers to light candles for lost loved ones. The candles mirrored the thousands of dots of blood from which my adjacent artwork is composed. I had dedicated the piece to a friend who lost both parents to COVID-19 during the first week of 2021. This friend visited our exhibition with two of her sisters. After lighting two candles, they took seats in the room and spent a considerable time there, in silence. Later, they shared stories with me about their mother and father. We laughed and we cried together in front of the artwork.

This was truly encouraging: that a work of art can bring people together in such a way and that, through the aesthetic curation of a rather utilitarian space, these visitors felt comfortable to share so intimately. It was holy.

Get the latest issue in print or subscribe for the next three.

The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge. Charity registered in England and Wales. Charity Number: 1191741

Kirby Laing Centre, Office 1, Unit 6, The New Mill House, Chesterton Mill, French’s Road, Cambridge, CB4 3NP

© 2025 The Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology in Cambridge